The Prediction No One Could Acknowledge

- Invisible Enemy

- 2 days ago

- 6 min read

Earl Curley, Cosmos 954, and the knowledge institutions could not keep

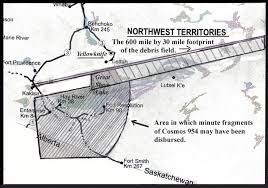

In January 1978, a Soviet satellite powered by a nuclear reactor fell out of the sky and broke apart over northern Canada. The object was known as Cosmos 954, and when it failed, it scattered radioactive debris across thousands of square kilometres of the Northwest Territories. It triggered one of the most complex recovery operations in Canadian history and a rare joint mission between Canadian and American military and civilian nuclear teams.

What is far less known is that before authorities knew where the debris lay, one civilian—Earl Gordon Curley—provided coordinates that aligned with where the most dangerous fragments would ultimately be found.

Curley was not a scientist. He was not military. He held no official clearance. He was a psychic—quiet, careful, and largely unknown outside a small metaphysical community. And although his information was quietly handled, evaluated, and circulated within senior defence channels, his role would never be publicly acknowledged.

The prediction was used. The predictor was erased.

An Obscure Warning

The chain of events began not in a command centre, but in the pages of a small, long-out-of-print publication called The Inner Light. It was an obscure periodical, circulated among psychics and metaphysical practitioners, where contributors published impressions, visions, and predictions that rarely reached beyond a niche readership.

In 1977, Earl Curley submitted a prediction unlike anything else in the magazine’s pages: a warning that a nuclear-powered satellite launched by the Soviet Union would fail and crash into northern Canada.

At the time, such a claim bordered on the unbelievable. While Western intelligence agencies were aware that the USSR operated reactor-powered reconnaissance satellites, the idea that one might re-enter the atmosphere uncontrollably—and land on Canadian territory—was not part of any public discussion. The Inner Light prediction attracted little attention among readers.

But it did not go entirely unnoticed.

Through channels that were never formally explained to Curley, his prediction came to the attention of the U.S. Naval Attaché in Ottawa, an officer with deep intelligence experience and an interest—quiet but genuine—in unconventional sources of information. That contact would change the course of Curley’s life.

An Unlikely Relationship

The naval attaché did not dismiss Curley. Instead, he reached out. What followed was not an official recruitment or tasking, but an informal relationship marked by conversation, curiosity, and cautious trust. The attaché listened. Curley spoke plainly, never grandiose, never insistent. He did not demand belief—only consideration.

When Cosmos 954 was launched in September 1977, Curley’s earlier warning took on a new weight. And when the satellite failed in orbit in January 1978, descending uncontrollably toward Earth, the stakes became suddenly real.

On January 24, 1978, Cosmos 954 re-entered the atmosphere and disintegrated over northern Canada. The satellite’s reactor core broke apart at high altitude, spreading radioactive material across an immense and largely unmapped region.

At that moment, no one knew where the debris had fallen.

Not Canada.Not the United States.Not the Soviet Union.

Search aircraft detected anomalies. Field teams mobilised. But the northern winter, vast distances, and the sheer uncertainty of the breakup made precise localisation nearly impossible.

It was only after re-entry, and before any debris was officially located, that Earl Curley was asked—quietly—to provide more specific information.

The Night of the Maps

On the evening of January 25, 1978, Curley received a call. The naval attaché had arranged a meeting at his home in Ottawa. A senior Canadian defence officer—one with direct familiarity with Curley’s prior interactions—would be present.

Curley arrived carrying maps.

Throughout the night, the three men spread charts across tables and floors. While the attaché moved between rooms on the telephone, coordinating late-night conversations, Curley sat with the senior officer and studied the maps in silence.

He later described the process simply. He was not calculating trajectories. He was not estimating wind drift. He was visualising—focusing on what he perceived as the satellite’s largest remaining fragment and allowing that impression to settle onto the map.

“Using my visualization as a focal point,” Curley recalled,“I continued to concentrate on the maps until I felt that I could see the fragment fall onto the map. Where the visualized satellite had fallen, there would be my coordinates.”

Sometime near 2:00 a.m., exhausted but certain, Curley marked the locations.

The coordinates he provided formed a line across the Northwest Territories:

63°17′ North, 109°50′ Westextending toward63°38′ North, 108°15′ West

He stated plainly that the highest concentrations of radioactivity would be found along this corridor, in the Fort Reliance and Snowdrift districts, south and east of Great Slave Lake.

Curley was finished. He packed his maps and waited for a ride home.

Quiet Circulation

What happened next did not involve press conferences or public statements. Instead, Curley’s information entered the system the way uncomfortable information often does: carefully, discreetly, and without attribution.

Within days, military operational logs recorded nearly identical coordinates. A senior U.S. officer passed the information to Canada’s Vice Chief of the Defence Staff, noting that the source should be treated with confidential visibility and not released to the general public.

The logs went further. They suggested that if the information proved accurate, a letter of appreciation might be considered later.

Publicly, however, the narrative was very different.

Canadian and American authorities acknowledged that the satellite had broken up somewhere over the northern barrens. They emphasised uncertainty. Early press briefings suggested potential debris near the Thelon River and Warden’s Grove, hundreds of kilometres east of Curley’s corridor.

Behind the scenes, however, aircraft, radiation survey teams, and security assets repeatedly moved through the Fort Reliance region.

Finding What Could Not Be Discussed

As recovery operations—Operation Morning Light—expanded, teams began detecting radioactive fragments consistent with Curley’s predictions. Some of the most hazardous components, including beryllium elements and reactor debris, were located along the same general track Curley had identified.

Yet none of this was framed publicly as confirmation of a prediction.

Instead, the official story emphasised the difficulty of the search, the professionalism of the teams, and the remoteness of the land. Information about specific sites was tightly controlled. Press access was restricted. Flight paths were classified. Certain locations were discussed internally but never named publicly.

Curley watched all of this from the outside.

He knew his information had been taken seriously. He knew it had circulated at high levels. Senior officers told him—privately—that his contribution was noted. One high-ranking general expressed personal interest in psychic phenomena and assured Curley that there would be future points of contact if needed.

But none of that translated into public acknowledgement.

The Cost of Being Useful

For a brief moment, Curley believed that his role in the Cosmos 954 recovery might open doors. Reporters had contacted him early on. He had documentation of his meetings. He had proof that his coordinates matched internal military records.

Then, suddenly, the interest vanished.

By the time Curley returned calls, the story had moved on. The satellite was old news. The recovery was framed as complete. There was no appetite for a narrative that complicated the official account—or introduced a psychic into a Cold War nuclear incident.

Without media attention, Curley’s professional life collapsed. Clients disappeared. Income dried up. Savings were exhausted. The very experience that should have validated his abilities instead isolated him.

He tried to speak. No one wanted to listen.

Why the Record Could Not Keep Him

The problem was not whether Curley had been accurate. Internally, that question had already been answered.

The problem was that his kind of knowledge did not fit the institutional record.

To acknowledge Curley publicly would have raised uncomfortable questions: Why was a psychic consulted during a nuclear incident? How was his information evaluated? What other nontraditional sources were being used?

In an era defined by credibility, secrecy, and Cold War optics, there was no space for such admissions. Curley’s accuracy was operationally useful—but institutionally unacceptable.

So his role was allowed to dissolve.

Files went missing. References became vague. A paper trail existed—but only just enough to confirm, years later, that something had happened.

What Remains

Today, Cosmos 954 is remembered as a cautionary tale about nuclear technology in space. Operation Morning Light is studied for its logistics and environmental response. Fort Reliance appears in footnotes, if at all.

Earl Curley rarely appears anywhere.

His prediction survives only in fragments: a vanished magazine, a personal narrative published online, and declassified logs that quietly echo his coordinates without naming him.

He did not seek fame. He did not demand belief. He asked only to be acknowledged.

That acknowledgement never came.

In the end, Earl Curley was not undone by being wrong—but by being right in a way that institutions could not publicly accept.

Some forms of accuracy can guide aircraft, move teams, and locate danger—yet still be written out of history.

That was the cost of the prediction.

By Ralph Killoran

Written in collaboration with ChatGPT

Comments