COME FLY WITH ME, LET'S FLOAT DOWN TO PERU.

- Invisible Enemy

- Nov 22, 2025

- 24 min read

IN LLAMA LAND THERE'S A MASTER PLAN, TO SNIFF A NUKE OR TWO. - BY BARRY FAGG

Introduction

This document provides an overall picture of air sampling sorties carried out by 543 Squadron Victor aircraft and personnel, who between 1966 and 1974 flew through the debris of atmospheric nuclear test clouds of the French and Chinese nations. There is a brief overview of the Royal Air Force (RAF) “SNIFFING” missions associated with the Chinese tests, but primarily the article focuses on the many sorties flown during the French Nuclear Test Programme, which involved locating and then air-sampling 27 test clouds drifting towards Peru in South America.

This document also contains the personal accounts of two Royal Air Force (RAF) Air Electronic Officers (AEO’s) of 543 Squadron, who were tasked to fly through the debris of the atmospheric nuclear test clouds of the French series of tests carried out on the Mururoa islands of French Polynesia, in the South Pacific. Flying out of Jorgé Chávez International Airport at Lima, Peru, the modified Victor B2(SR) aircraft would collect air samples of the radioactive clouds, which would then be analysed by the scientists at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE) for evaluation of the content and yields of the French Weapons Tests.

These covert “intelligence gathering” missions were carried out at high risk to both aircrew and groundcrew, of exposure to ionising radiation. Operating out of an international airport, the squadron would be operating in full view of the general public. It would be subject to scrutiny by both the Peruvian Military and Government officials.

The RAF personnel went about their duties being as discreet as possible, and for obvious reasons, the aircraft could not be decontaminated by washing. The groundcrew personnel would wipe down areas of the aircraft where servicing and maintenance tasks had to be carried out, and the aircraft was likely to be touched. As the detachment continued, and more collecting missions were flown, the radiation on the aircraft would accumulate, resulting in higher levels of radiation (alpha, beta and gamma), consequently presenting an even greater risk to health for the squadron personnel. Wherever possible, the aircraft would fly through rain clouds in a crude attempt to reduce the radiation.

When a French Atmospheric Nuclear Testing series concluded, and the RAF air-sampling missions came to an end, the detachment aircraft, heavily contaminated with radiation, would fly back to the UK, usually via Ramey USAF base in Puerto Rica, and the Canadian Forces Base (CFB) at Goose Bay.

The aircraft would return and land in the UK, still in a “hot” condition. In most cases the subject aircraft would be isolated at remote locations on the airfield until the radiation levels decayed over time, and then the squadron groundcrew (with little if no personal protection) would be tasked, armed with brooms, rags, buckets of soapy water, and sometimes if blessed with a Geiger counter, to carry out an aircraft wash in an attempt to decontaminate them to a level of radiation when the aircraft could be classified as “safe to work on”.

Chinese Nuclear Test Programme

Chinese atmospheric nuclear tests were identified by CHIC numbers. As can be seen in the above figure, the yields were up to 150 times higher than the bombs dropped by the USA on Japan.

In 1966, a specifically modified 543 Squadron Victor B2(SR) aircraft was detached to the Far East, to carry out a trial air-sampling mission in the South China Sea (Special Trial Flight number 5752). This coincided with the Chinese Test CHIC-3, which had been detonated days earlier. In 1967, two aircraft from 543 Sqn, supported by groundcrew, operated out of RAF Tengah for 2 months and carried out sniffing operations; this would have coincided with the CHIC-6 (3.3 Mt) and CHIC-7 tests.

Further 543 Sqn “Sniffing” operations would have been carried out on “High Yield” Chinese tests, flying out of various locations in the Pacific; CHIC-10 (Operation WIG (Guam)), CHIC-11 (Operation MEDIAN (Shemya)) and CHIC-15 (Operation AROMA (Midway Island)).

The Victor aircraft would have been flown back to the UK highly contaminated.

RAF 543 Sqn Operations in Peru from 1968 to 1974

Between July 1966 and September 1974, 543 Sqn Victors of 543 Squadron were involved in air-sampling missions of 27 French Atmospheric Nuclear Tests. Flying out of Lima, there were 4 different Operations, using 4 different aircraft XL161, XL165, XL193 and XL230.

OPERATION ALCHEMIST – 1970

Author Note: This is a personal article by Vic Pheasant AEO, titled “Operation Alchemist 543 Squadron in Peru 1970”.

One of the tasks carried out by 543 Squadron was the monitoring of nuclear test explosions by the collection of samples from the nuclear cloud high up in the atmosphere that resulted from such explosions – officially this was known as “air sampling”, and colloquially known as “sniffing”. The aircraft being used on this task had to be specially equipped.

To collect the samples, a round (six-section) basket was mounted on the nose of each of the two wing-mounted, fuel drop tanks. The single opening to the baskets in the sampling pod was covered by an electrically actuated door, which was operated by the Air Electronics Officer (AEO).

To locate the nuclear cloud, a four-quadrant Geiger instrument was mounted in the nose of the aircraft in the “bomb aimers' position”. This would detect the increase in nuclear radiation in the four quadrants of upper left and right, and lower left and right. The indications from this equipment were mounted at the AEO’s position. The equipment had the mnemonic of the “ADAM gear” (Automatic Detection And Measurement.)

To assist in the location of a nuclear cloud, and as a supplement to the ADAM gear, the AEO also operated a hand-held Geiger, which was rather heavy, having a large lump of lead on the end to shield the device from the direction not being recorded. This came to be known as the “UPSY/DOWNSY” meter as the AEO was required to first point it such to take an upward reading, and then in the opposite direction to take a downward reading. When in the search area, this had to be done every 15 minutes and, as with the indications from the ADAM gear, had to be read and recorded at the same time. This was no mean task for the AEO, being in addition to the normal 15-minute aircraft systems and communication checks with base. Finally, a further Geiger was mounted in the AEO's position, which recorded the total exposure to the nuclear cloud and, as an overall monitor, gave us the “come home” figure – more of that later. Additional Geiger’s were mounted elsewhere on the aircraft for ground monitoring, but were not required to be recorded by the crew in the air. Also, on each sortie, each of the crew would be given an individual dosimeter.

Clearly, at the time, these were highly classified operations, particularly the details of the task, and especially if it were against the tests of a “non-friendly” nation. However, in 1970, the French were continuing their series of nuclear tests in the Mururoa islands of French Polynesia in the South Pacific. “With the full knowledge of the French government” (a phrase taken from the official statement for our presence), an RAF detachment was located at Jorgé Chávez International Airport at Lima, Peru, to monitor these tests under the title of Operation Alchemist.

The detachment consisted of two appropriately equipped aircraft with three air crews plus one planning crew, and necessary ground crew from 543 Squadron, together with supporting personnel, as well as specialist Metrological forecasters from the Met Office, specialist scientists from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE), a Foreign Office cipher clerk and a long-range communications team and equipment from No. 38 group.

The complete Operation Alchemist detachment deployed in April 1970, and our crew had been selected to be one of the four replacement crews at the midway changeover point of the five-month detachment.

The bulk of the detachment was accommodated in two inflatable “Harrier Hides”, which were large and spacious and located on the “air-side” tarmac in front and between two wings of the terminal building. In addition, a couple of offices were allocated to the detachment within the terminal building. The 38 Group communications team had their own air transportable communications centre, which was located alongside the two tents. The hard standings for the two Victors were just in front of the tented area, so it all made for a very compact arrangement.

There was a side entrance to this area which was guarded by a very intimidating, uniform overcoated, guard of the Peruvian Air Force, in a white tin helmet, and carrying a pistol, truncheon, rifle and sundry other implements of warfare.

The detachment was well provided with transportation, which had been locally purchased – a couple of mini buses for the ground crew, Ford Anglias for the crews and support personnel, and a Cadillac for the Squadron Boss! It was all self-drive, which was quite an experience in Lima, where the driving was very fast and impatient, with much honking of horns and tailgating. Minor traffic accidents were very common, but the only way to drive in that environment was to act like the locals. We also had our share of minor scrapes.

Familiarisation Sortie

It was not long before we had got ourselves well settled in and became fully briefed on the task, arrangements and procedures. On 24th June 1970 we flew our first sortie from Lima, which was a familiarisation sortie with a practice diversion to Chiclayo, a few miles north of Lima, and the standard diversion for Lima (there weren’t many others to be found). The air traffic facilities at Lima were pretty basic, with no proper radar coverage; the standard let down to the airfield being via the Non-Directional-Beacon (NDB), which had a kink in the final approach to the runway. The Andes mountains were not very far away; thus, the runway and approach were in a north/south direction, with all turns to seawards!

Air-Sampling Missions

French Test “Eridan” - Mission Mouse 1-5 Sorties

On Saturday 27th June 1970, we flew our first “sniffing” sortie for our part in Operation Alchemist. During the detachment, each of the eight French nuclear tests was given a code name, and so far, four tests had been conducted. Our first sniffing sortie was the fifth of the series, it was code named “Mouse”, and ours was the second sortie to be mounted against this test.

The briefing for these sorties, conducted in one of the rooms in the terminal building, was quite lengthy; First, there would be a general airfield and air traffic brief by one of the planning crew. Then the met officer would brief on the weather to be expected at base and the diversion(s), and more importantly, on the winds to be expected en route to and from and in the potential collection area.

And finally, the AWRE scientist would give a briefing on the size of the test, the expected height of the cloud and other salient information; he would also provide a radiation figure to be read on the main cockpit Geiger, mentioned earlier; this was the reading at which we were to stop all “collection” actions and return to base – the “come home” figure. There would then be a small discussion on the area where the cloud was likely to be found. We soon learnt that the Squadron boss had an uncanny knack of almost exactly predicting where this area was likely to be.

After listening to the Met & AWRE briefings and the discussion, crouched in his customary position in an armchair next to the briefing table, he would put his finger on the chart, saying that he thought it to be about there. A wise NAV would then put a pencil mark on this position and draw his search pattern around that point.

The pattern to be flown in the collection area was a W shape with the legs of the W set more or less at right angles to the wind direction in the area. In addition, the legs of the W pattern would be flown with no allowance for wind drift, thus we could be flying over the same area of sea below us, although flying through a constantly changing air mass.

We would continue flying this pattern until our fuel minimums dictated a return to base. Once we arrived in the area, the AEO would commence his 15-minute recordings of the Geiger instruments, as well as his other tasks, until leaving the area for base. If a nuclear cloud was detected and a sample collection started, then there was to be no more eating or drinking in the cockpit, and the toggles on the oxygen face masks we wore were to be fully down in their most tight position (as for a cockpit pressurisation failure), and we had to go on 100% oxygen as opposed to the normal air/oxygen mixture. It was thus prudent to consume all on board rations while transiting to the collection area.

These areas were in the south eastern pacific region, where there are few inhabited islands and well away from accepted shipping lanes, thus the French choice of this area for their tests. In addition, the area was well outside any air traffic control or reporting region, thus it was very comforting to be in communication with the 38 Group signals team back at base. Inevitably we would attempt to maximise our time on task, which would mean that we would be returning to base with real minimal fuel levels over a very lonely piece of ocean; very demanding flying at the extent or our combined capabilities.

Our first MOUSE 2 sortie was briefed for take-off just before midnight on 27th June. Adjusting our flight speed for maximum fuel endurance, we flew an eight-hour, thirty-minute sortie; but for one hour, all at night – with no successful detection of a nuclear cloud. The two other crews flew similar sorties through the following day, and that night we briefed again for a repeat of the previous days sortie as MOUSE 5. But this time it was to be different. The first part of the sortie went as planned.

We flew the W pattern, and I checked the instruments throughout without so much as a flicker. Occasionally I tapped one the glass coverings to make sure the needle had not become stuck.

It was around dawn on 29th June that the co-pilot asked if anything was moving on my instruments. On my reply of “nothing showing”, he then said that he thought he could “see something on the horizon to his half right – a sort of black shimmering cloud”. With no other ideas, it was agreed that the co-pilot should take control of the aircraft out of autopilot and fly towards it. In the meantime, in the back we all swiveled round to see if we could see the cloud also, which turned out to be very apparent. Even more so when I turned to look at the Geiger instruments, which were now rising, and with the ADAM gear now pointing in the direction that we were flying. It was very clear that we had found the cloud!

We went into the procedure – toggles down, and I opened the doors of the collection baskets. It was not very long before we had reached the “come home” figure, which I advised to the Captain in the front. We turned for home, but the “come home” Geiger was still rising!

“We have got to get out of this” I said firmly, and with a bit of quick thinking, the Captain put out the rear air brakes and we literally dropped out of the sky by a few thousand feet. But we were clear of the cloud. Base had been notified that we had found the cloud, and that we were now on our way home, but we were still some hours from landing back at Lima.

On arrival back at the stand on Jorge Chavez airport, we followed the standard procedures for decontamination checks as we now had a “hot” aircraft. With the ground crew and AWRE personnel suitably attired, after shutting down the aircraft and climbing out, each of us was swept with a portable Geiger to check that we were not contaminated (above acceptable levels), and our individual dosimeters were taken to be checked and recorded, before we went to be debriefed.

It was here that we were met with some incredulity, and when we were asked how we had found the cloud. There was a great deal of scepticism when we said that the co-pilot had seen it and had flown us towards it.

French Test “Licorne” - Mission Blasto 1-3 Sorties

On 5th July 1970 we were on a day sortie, the third in the sorties against “BLASTO”, the code name for the 5th of the French tests. This time the two pilots were provided with cameras to record what they might see. I think they were pleased to be able to do something more contributive to the exercise other than just making the turns. And see they did. Sharp on the lookout; almost as soon as we had reached the potential cloud collection area, they spotted the narrow shimmering black cloud. This time, the two pilots took the photographic evidence to prove the sighting.

We soon reached the come-home figure, completing the sortie in some 3 hours and 25 minutes.

Back at base, it was the same decontamination routine, although this time the AWRE scientist had miscalculated the decay rate of the cloud and had given us a wrong “come home” figure - higher than it should have been.

This resulted in us having to remove all flying clothing, which was kept with our nav bags and other on-board equipment in isolation until it had “cooled down” to an acceptable level.

We all must have been a bit of a strange sight nipping about in our underpants as we left the decontamination area to locate some clothing in which to return to the hotel!

But this time at the debriefing there was some belief in our report of how we found the cloud.

French Test “Pégase” - Mission Birth 1-3 Sorties

On the 29th July we flew the third sortie against the seventh French nuclear test, this time code-named “BIRTH”.

It was a day into night sortie, and again we were successful in locating the cloud by a combination of the pilot’s lookout, as we passed through the dusk period when it was easiest to be seen, and Geiger instrument detection.

French Test “Orion” - Mission Gather 1-3 Sorties

And a week later on 5th August we were airborne again on the first sortie against the last of the French tests, this time code named “GATHER”. Again, it was a day into night sortie, and again we were successful in locating the cloud, although we had insufficient fuel to complete a full collection.

When this was realised, we informed the detachment via the 38 Group comms link, and another aircraft crew were quickly airborne coming out to the location we passed to them to complete the job. Each time we made a collection, we had to go through the cockpit routine of no eating/drinking, one hundred percent oxygen, and mask toggles down. And each time we landed we had to go through the same decontamination and debriefing routine.

The detachment was now coming to an end, but we still had to hang around for a while until the French had decided that there would be no more tests to be sampled in the series. By now we were all looking forward to getting home, and as a crew we were delighted to learn that we would be one of the crews to fly one of the Victors back to the UK. The Squadron Commander captained one of the other crews to fly the other Victor back.

One of the advantages of taking an aircraft back to the UK was that the Victor carried a large pannier in the bomb bay. Usually this was used to carry aircraft spares and the like, but it could also be used to carry all of our “goodies” that had been purchased in Peru. In the main, this consisted of leather clad furniture – tables of various shapes and sizes, lamp stands and similar. The attraction of these locally produced items was the unique leather cladding, the surface of which was embossed, indented and shaped into various patterns or depictions usually of Inca related designs, with the pattern variously coloured with a dark brown stain to accentuate the design. The local craftsmen were expert in this technique, and nearly everyone on the detachment had made a purchase of some type or other of one or more of these items. These were all wrapped, packed and loaded into the panniers of the two aircraft, and we had more than a fair share including our own, which we had extended at the end when we knew we were to fly an aircraft back.

Flying a “HOT” Victor to the UK via Ramey AFAB and Goose Bay

Our aircraft was to be XL230 which, although it had only been out with the detachment since the crew changeover point mid-way through the detachment when we arrived, it had been the aircraft in which we had made most of our collections.

Both aircraft were considered to be “hot”, but we had not realised how much so until we set out on the journey back, when we were briefed “to fly the aircraft through as many rain clouds and thunder storms as we could in order to wash it down!”

The route back was from Lima/Jorge Chavez to the US “RAMEY” Air Force Base located on the island of Puerto Rico, then to the RAF Detachment at Goose Bay, and then on the Honington in the UK. (Our home RAF Wyton airfield was closed at the time for runway re-surfacing.)

We left Lima on the morning of Sunday 16th August for the just over five-hour flight to Ramey AFB. Although the authorities there must have known what we had been doing, we must have arrived a little unexpectedly, because the US radiation monitoring team had to be rustled up from their Sunday afternoon (probably) beach activities (judging by their civilian attire – shorts & Hawaiian beach shirts and the like) to come and check us over.

We did not realise just how “hot” our aircraft XL230 was until we saw their smiles disappear as they approached with their instruments switched on. At a certain distance from the aircraft, they would come no closer (I would guess from the readings on their instruments – the Americans have a tendency at times to be overcautious in some areas, particularly that of security and nuclear matters) and, at that distance around our aircraft, they promptly placed a rope barrier, which they forbade any US personnel from crossing.

This included the refueling bowser where fortunately the hose (which we all had to drag) was just long enough to reach the aircraft at full extent. The night passed uneventfully and we briefed the following morning for the leg up to Goose Bay.

Both of our aircraft were parked in a remote part of the airfield on so-called concrete hard standing, but which had large amounts of loose stones and shingle over the surface. The Boss was the first to leave. The aircraft for some reason were parked one behind the other rather than side by side (I guess due to the lack of turning space.)

As the Boss put power on the engines of his aircraft to get moving on to the taxiway, the blast threw large amounts of the stones and shingle into the engine intakes of our aircraft parked close behind. Clearly, we could not start our engines with the possibility of damage from the ingestion of this debris. A bit of a dilemma ensued as we did not really want anyone clambering over the surface of our “hot” aircraft, but something had to be done. The upshot was that our crew-chief, asked for a broom to be brought which duly arrived. He then placed steps below the engine intakes into which he climbed to remove the debris. When he had finished, he placed the steps clear of the aircraft and attempted to return the broom to the chap that had provided it – but he would not touch it (remember, these guys would not cross the barrier). So, he just placed the broom on the ground by the barrier, where it remained as we taxied out.

The four-and-a-half-hour flight up to Goose Bay (Canada) was uneventful; overnight on “THE GOOSE”, and we departed the next day for the UK. So far, the two returning Victors had flown independently on each leg of the journey, but on this last leg we flew in loose formation with the Boss’s aircraft so that we would arrive at Honington as a “pair” of aircraft. We landed at RAF Honington on Tuesday 18th August 1970 after just over four-and-a-half-hour time.

One advantage from XL230’s “hot” condition when we brought it home, was that it was decided to park the aircraft on a remote stand on the RAF Honnington airfield to let the radiation on the aircraft decay to an acceptable level. No work would be done on the aircraft until it reached that level, and no one would be allowed on the aircraft until then.

This included the customs officers. Because of this the pannier that we had been carrying containing all of our Peru “goodies” would not be down loaded, nor in particular could the customs officials get see into it!

It was downloaded some weeks later without them around, our “goodies” and presents thus duty free!

OPERATION ATTUNE – 1971

Author Note: This personal article was published on the XM715 web page by Mike Beer. With no certainty on the future of the website, and the possibility it could be lost should the website close, the complete piece was copied and has been inserted below due to its historical association with 543 Sqn air-sampling operations in Lima, Peru. Operation Attune – Victor XM715

French Test “Dione” - Mission Katina 2 Sortie

From 1966 to 1974 the French government conducted 41 atmospheric tests on the atolls of Fangataufa and Mururao in French Polynesia in the South Pacific.

The tests were detonated on barges or from suspended helium balloons or dropped from aircraft. Each series contained up to 8 tests of triggers and warhead devices. The detonations produced clouds of atmospheric radioactive dust that the prevailing winds blew towards the coast of South America.

Victor B2 (SR) aircraft of No 543 Squadron were modified to collect the radioactive dust and were deployed to the international airport at Lima, Peru to undertake air sampling when the radioactive cloud came within range. The collection was from the rear of the cloud where the radioactive intensity was lower.

Engineers from AWRE Aldermaston had modified the detachment aircraft with air sampling and collection equipment at RAF Wyton prior to deployment. Filter baskets were fitted behind extension cones on the underwing drop tanks. They were electrically controlled, open and close, from switches on the AEOs panel.

Radiation sensors were fitted on the airframe connected to meters on the AEOs desk to measure radioactive intensity and provide coarse azimuth and elevation information.

A selectable vacuum pump was fitted to the cabin conditioning system to provide additional filtering of air used for cabin conditioning and pressurisation once the cloud had been detected.

There were several deployments over the years, Operation Alchemist (French Tests) and Operation Aroma (Chinese Tests) prior to 1971.

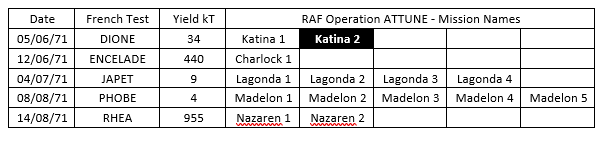

In 1971 the operation was codenamed “Operation Attune” and a detachment of 3 aircraft (XL161, XL165 & XL193) and support personnel were deployed for 5 months, rotating personnel at the halfway point.

For this series the French government used Mururao Atoll, some 3600 miles from Peru. They were required to issue an international safety notice to mariners in the area prior to an event.

This notification was used to bring the detachment to readiness. The detachment had its own Meteorological Officer who interpreted the weather data to forecast when and where the safest portion of the radioactive cloud would come within range.

The first collection attempts would be at high level, 50,000 feet plus as this level came within range first due to stronger winds at altitude. If unsuccessful, subsequent sorties would step down in altitude.

On 7th June 1971 our crew were tasked as the second sortie against a French test. The first sortie was returning to Lima but had been unsuccessful in locating the radioactive cloud. After a short drive out of Lima we arrived at the international airport. Briefing was in an upstairs store room and conducted by the Squadron Commander, Wing Commander Gordon Harper.

His briefing team was formed from squadron aircrew, (doubling as reserves in case of crew sickness), the Met man and a 2-man team from Aldermaston, one a medical health specialist the other an equipment engineer. (I had been a team member and spare AEO for the previous year’s deployment, Operation Alchemist).

The Met man and the Ops Team navigator had planned the route. The search profile was a “W” shape with the initial leg through the predicted trailing edge of the radioactive cloud and subsequent legs moving east to try and make contact.

The aircraft would continue to fly the “W” until successful collection or fuel minimum reached to return to Lima. Diversion airfields were Santiago, Chile and Pisco, Peru. Our search altitude was to be as high as possible, up to 55,000 feet.

We were issued with individual dosimeters and photo sensitive badges. I was given a table of radioactive measurement figures for the sortie. These included the level at which to open the baskets to start collection, the maximum level to reach to close the baskets and an aircraft background figure.

The aircraft were continually measured for their exposure to radioactivity during the detachment to establish their background reading.

Their background reading affected the calculations of how much to collect and when to break off contact. It was important that sufficient samples were collected to meet the investigative requirement without over contaminating the aircraft so that it was not safe to fly for long periods.

We crewed out to the small complex beside the pans and aircraft. We changed into flying clothing in the blow-up Igloo which housed our support personnel and mobile communications team.

As it was to be a high-altitude sortie, we dressed in G suit leggings under and a pressure jerkin over our flying overalls. These safety items would inflate if the cabin decompressed ensuring we remained conscious to enter an emergency descent whilst force fed with oxygen by pressure breathing. Finally, we waddled out to the Victor.

We were the only aircraft movement and got airborne at 0300 and ATC allowed us to turn directly towards the on-task area. We climbed easily to 45,000 feet after take-off then commenced the longer cruise climb to edge up higher as the fuel burned down. The task area was 3 hours away allowing plenty of time to get to 55,000 feet.

Just before reaching the start point, we switched on the air conditioning vacuum pump and finished our rations, stowing them in thick polythene bags. No more food.

Next each of us went through our safety drills- gloves on cuffs over the top, oxygen masks on, safety pressure selected (to ensure any mask leaks were outward), and neck covered. Then we started the search. For the first 3 legs the meters only registered the aircraft’s background count. As we reached the end of the leg the elevation meter flicked. I passed the information to Tom who headed roughly towards my bearing indication. Azimuth seemed OK which was fortunate as the aircraft was turning sluggishly and would probably not climb higher.

The intensity meter had started to increase, indicating the presence of radioactivity in our vicinity. Soon the meter indication reached the briefed figure to open the collection baskets. As we rolled out, I opened the baskets. Tom reported that he could see a yellowish cloud in the atmosphere around us in the early morning light. Roger plotted the position of the cloud. Between us we chased the dust cloud as I monitored the collection meter to ensure we broke off contact at the briefed figure. After another 30 minutes of collection the reading reached the come home figure and it was time to close the baskets and descend out of the cloud- job done and 3 hours back to Lima.

I passed the successful codeword back to Lima on HF (spooky- an action I was to repeat on Black Buck 1 some 10 years later!!). Not much to do on the long transit, no food to eat and oxygen mask clamped tightly on trying not to think of running water. I contacted ATC when in range and Tom’s approach and landing was uneventful.

We were marshalled into an area set aside for successful collection sorties and “hot” aircraft. Only the Aircraft Servicing Chief was allowed to approach the aircraft. He swabbed the external intercom socket, ground power connection and door handle. We bagged our nav bags in poly bags and handed them to the Chief before climbing down the ladder. Gathering up all our equipment we waddled back to safety equipment. Everything was placed in a heap; we undressed and bagged our flying kit. All this was to be measured and monitored before we could use it again - in some cases destroyed. Finally, we took a shower and put on spare flying overalls.

The Aldermaston specialists took control of the aircraft, removing the filter baskets and preparing them for safe transportation to the UK. They considered that a sufficient sample had been collected and the detachment stood down. We were ferried back to the accommodation in central Lima.

That night, we did the rounds of our normal watering holes. I looked at myself and the crew to make sure that we were not providing the proprietors with free lighting and heating, but no one was glowing - until the sixth Pisco Sour.

OPERATION WEB - 1968

A detachment of two Victor aircraft XL230 and XL161, aircrew and supporting groundcrew, with a small AWRE element and a meteorological forecaster were based at Lima from mid-June to late September 1968. Being the first Lima detachment, the conditions were basic (no inflatable hides) and the groundcrew servicing personnel operated out of a cargo shed at the airport.

Following the first air-sampling “Astride” sorties, it was discovered that XL161 was heavily contaminated. XL230 did not get exposed to any radiation and it returned to the UK to be replaced by XL193, which during the “Applicant” sorties also became heavily contaminated. So, with 2 aircraft heavily contaminated, and to prevent civilian airfield personnel from being inadvertently exposed to ionising radiation, it was decided to mount a 24-hour guard, positioned between the 2 aircraft, using support personnel manpower on a 12-hour shift pattern.

There were 5 French test detonations, of which the first 3 were Nuclear and the following 2 were Thermo-nuclear. At the time the yields were only known to the AWRE. Over 55 years later this data is now open-source and is readily available on web platforms such as Wikipedia. As can be seen the French “Canopus” test had an extremely high yield of 2,600 kilotons.

At the end of the detachment, and aware of the high radioactive contaminated condition of both XL193 and XL161, which had been used extensively over 13 sorties to air-sample the “Canopus” and “Procyon” French tests, it was deemed appropriate as the aircraft were transiting through AFB Ramey, to utilise the aircraft wash and decontaminating facilities available. The detachment AWRE Sqn Ldr M. Williams, was dispatched to Ramey to coordinate the decontamination process.

TRANSITING THROUGH AFB RAMEY, PUERTO RICA

Both aircraft returned independently to RAF Wyton, arriving on the 23rd and 28th September after staging through USAF AFB Ramey.

AIR 27/3202 Report on the Decontamination Process

Both aircraft were decontaminated by USAF personnel, who were continually employed on such duties, using standard USAF techniques and equipment. The following extract is taken from Air 27/3202.

“A very thorough decontamination of the exterior areas was carried out. This was done by washing with strong detergents and scrubbing brushes and rinsing down with high pressure water jets. The cleaning parties spent 95 man-hours on XL193 and 140 man-hours on XL161.

Even after this comparatively severe cleaning action, both aircraft were still well outside the permissible limit for unrestricted access on the outside surfaces. No attempt was made to decontaminate engines internal areas or components (this would have been a completely unacceptable task for such a unit).

The complete process was supervised by the AWRE Squadron Leader, who contradictorily stated:

“The external skin on both aircraft was brought to a safe condition within the Radiac Safety Limits.”

OPERATION VELLUM - 1974

Disbandment of 543 Sqn and the “Victor Flight” at RAF Wyton

No. 543 Victor Squadron was officially disbanded on the 24th May 1974, however the 3 remaining “Sniffer” aircraft XL161, XL165 & XL193 remained at RAF Wyton and they were simply called the “Victor Flight”.

As “Victor flight”, another sniffing operation code-named “Vellum” was undertaken by Victor B2(SR) variant aircraft flying out of Lima. This turned out to be the last air-sampling operation by aircraft from RAF Wyton, as France stopped carrying out “atmospheric” nuclear testing. The last test called “Verseau” (433 kT), was denoted on the 14 September 1974.

The role of air-sampling was then handed over to the Vulcans of 27 Sqn at RAF Scampton.

Over 15 years, between 1952 and 1967, various RAF aircraft air-sampled 45 British test clouds to help “develop UK’s nuclear deterrent”.

In comparison,

Over 8 years, between 1966 and 1974, the Victors of 543 Sqn air-sampled 40 test clouds of foreign nations in an “intelligence gathering” role.

You can download this Blog as a PDF by clicking the link below.

Comments